Bornean Orangutan have strong family ties, with females playing a vital role in each community. Read on to find out about the family tree of a very special group whose habitat you can help protect through our latest appeal. Credit: chrisperrett.com.

All animals need habitat to thrive but the bond between an orangutan and their rainforest home runs especially deep. This is a species where related females share their ancestral land for life and Malaysian Borneo’s Kinabatangan, the landscape you can help protect through our new appeal, is no exception.

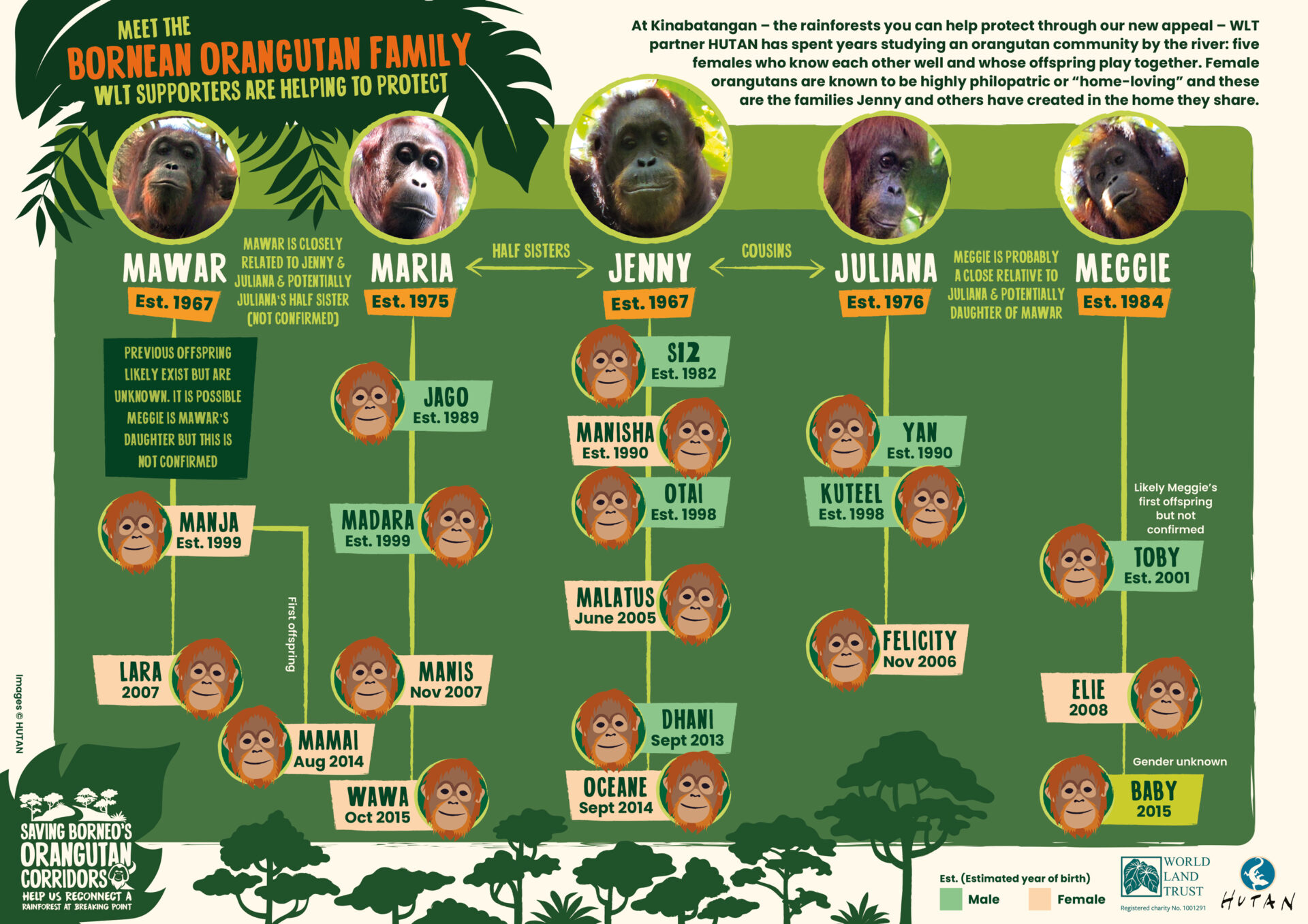

Thanks to the HUTAN researchers who have spent decades observing these great apes, today we can bring you the family tree of a very special community – the orangutans that HUTAN knows as the “Front Side River” family group.

Jenny, Mawar, Maria, Juliana and Meggie – as the family tree below illustrates (click on the image below to explore it in full view), these five Bornean Orangutan females have been for years the beating heart of a community by the Kinabatangan River.

The five female orangutans that carried on the family line in Malaysian Borneo’s rainforest hold a very special place in our partner HUTAN’s heart – they are the reason HUTAN has worked to protect this habitat for 23 years. Credit: WLT/HUTAN.

“Females are the anchor of every orangutan population,” says Dr Felicity Oram, part of the team who has been documenting this family group for years. “These communities of maternal relatives and their offspring actually lead quite interconnected lives around the spot they grew up in. Their female-centred ‘villages’ are scattered across the wider forest and visited by the more nomadic adult males, who tend to travel through the landscape following fruiting patterns.”

While females are far more home-attached than males, a fair bit of roaming can still be expected within the general area of a community. “The map below outlines the space and routes used by each female in what we call the ‘Front Side River’ family group,” Felicity explains. “These roaming ranges overlap and shift as the community accommodates newly maturing young females. It’s quite a well-defined group, however, and non-related females who might try to join in would not be met by much hospitality by those who already live here.”

HUTAN researchers first managed to gain the trust of orangutan matriarch Jenny and through her, a window was opened over the years into the movements of a community of related females. Credit: HUTAN

The years of tracking the comings and goings of these five females have yielded unforgettable moments for HUTAN’s researchers. Felicity recalls an instance where matriarch Jenny refused to continue sharing a nest with daughter Malatus when she was about seven years old, the typical age for a young orangutan to transition from full maternal reliance to semi-independence.

“This being the first time Malatus slept on her own, we decided to monitor the situation,” Felicity says. “After Malatus had built her own nest and settled in for a first night in her own bed, we saw Jenny briefly peek over from her own nest about 20 metres away, as if to quickly make sure that all was well.”

Particularly key for orangutans, Felicity adds, were scientific studies initiated in 2001 in the Kinabatangan that helped establish that females are highly philopatric – a term derived from the Greek roots philo (liking, loving) and patra (homeland) used to describe species that tend to stay in or return to the area of their birth.

“These findings underpinned our own behavioural studies and helped us understand, over the years, just how crucial it is to preserve land where these wild females are still living and raising their babies – and how important it is to protect and expand this space for the next generation if populations are to stay viable in the long run,” the HUTAN researcher explains.

In the Kinabatangan Floodplain, populations of orangutan have dropped by over 95% in the last century but our partner HUTAN has a plan.

For decades they’ve been saving and restoring these rainforests, and this year WLT is helping fund new purchases through our ‘Saving Borneo’s Orangutan Corridors’ appeal. In the days since we launched the campaign, donations by WLT supporters have already allowed to come within touching distance of the initial £150,000 target – and now HUTAN can save two plots of rainforest.

This incredible response to the appeal, beyond anything we had hoped, means we can now go further and faster for the home of orangutan. By doubling our target to £300,000, we can fund HUTAN’s purchase and protection of other plots of rainforest sooner than we had thought it would be possible.