Well, you’ve done it again! Today we’re delighted to bring you news of the latest fully funded World Land Trust (WLT) appeal. The WLT team, our partner Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) and the A’chik Mande people of the Garo Hills would like to thank all of you have brought Project Mongma Rama to its successful conclusion. The appeal may be finished, but the impact you’ve made in northern India’s Meghalaya State will be felt for years to come. Read on to discover your new role in an enduring conservation legacy.

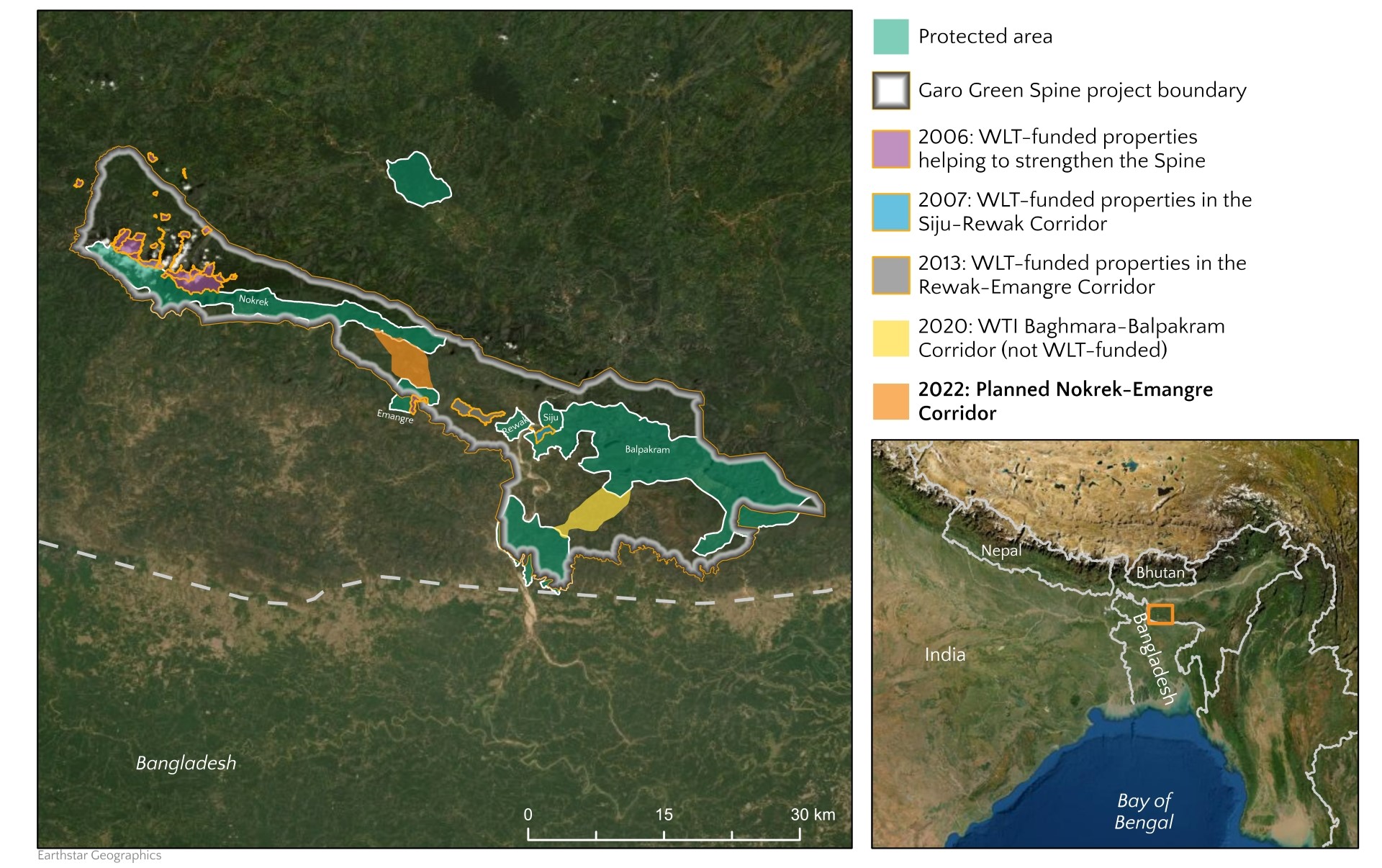

By raising an incredible £350,000, you’ve ensured the next crucial stage of WTI’s Garo Green Spine project will now go ahead, bringing a multitude of benefits to people and wildlife alike. WLT supporters had already established two elephant corridors here in years prior (with a corporate donor adding a third), stitching together Garo’s network of protected areas – the “spine” that makes this place so special. Now, with funding secured for a fourth and final corridor, 20 years of work has come to fruition.

This significant milestone, made possible by your generous donations, builds upon a long line of achievements stretching back to 2003. The three existing mongma rama – “elephant paths” – are part of a total 4,000 ha (9,800+ acres) set aside by local communities as Village Reserve Forests (VRFs). There are already 20 VRFs in the Garo Green Spine, monitored by 19 watchers hired from local communities, and 300 ha (740 acres) of degraded forest habitat has been restored by planting 250,000 native trees.

Project Mongma Rama is set to transform the Garo Green Spine once again. Here is what you’ve helped to make a reality:

- 4,000 ha (9,800+ acres) protected through community-owned reserves from 2021-2026

- 35,000 ha (86,000+ acres) protected under biodiversity-friendly community plans from 2021-2030

- 400 ha (900+ acres) restored by planting a total of 300,000 native trees from 2021-2026

- Five new watchers hired from local communities from 2021-2026

WLT supporters will directly fund around half of these outcomes: 2,000 ha of reserves, 15,000 ha of community plans, 170 ha of restoration and three watchers.

As you’ll see from the above map, the fourth and final Garo corridor, between Nokrek National Park and Emangre Reserve Forest, will fill the last significant gap in the Garo Green Spine network. With funding for this corridor now secured alongside all the other outcomes from our appeal, it’s worthwhile to take a step back and really appreciate what you’ve helped to create: an almost completely contiguous network of protected areas, close to 50 miles long from east to west, in one of the world’s most threatened biodiversity hotspots (the Indo-Burma).

The connectivity that the Spine provides is hugely important for roaming elephants, 1000+ of which are supported by the Garo Hills and the broader area in which the hills sit. Levels of human-elephant conflict in Meghalaya are lower than in most other Indian states, thanks largely to the amount of habitat available. The Nokrek-Emangre Corridor will help to preserve this coexistence, protecting the forests that the elephants depend on, away from human settlements.

Protected corridors support both female-led clans and wandering males, preserving the long-term genetic diversity of Asian Elephants. Credit: David Bebber

Elephants are one of 85 mammal species supported by the Garo Green Spine, and the local biodiversity doesn’t stop there: 206 bird species, 124 fish species and 62 reptile species have also been recorded in the project area. Keeping forests connected and intact is particularly important for species like the Endangered Western Hoolock Gibbon, India’s only ape, which spends most of its life in the trees, where it’s joined by the Capped Langur and Northern Pig-tailed Macaque (both Vulnerable).

Avian residents include the Crested Serpent-eagle, Greater Racket-tailed Drongo and Great Hornbill, the latter of which has a declining population that could halve over the next three generations, according to the IUCN. Garo’s forest floor is home to threatened species like the Sambar Deer and Greater Hog Badger, as well as Clouded Leopard (which require large territories) and the Chinese Pangolin (a Critically Endangered target of the illegal wildlife trade).

As a species that requires extensive tracts of undisturbed forest, the Great Hornbill is severely threatened by deforestation. Credit: AERF

With Project Mongma Rama, WLT and WTI are following the example set down by the people who have lived in the Garo Hills for over two millennia. Rangku Sangma is a member of the Garo Hills Autonomous District Council, an organisation set up to manage community-owned land here. As our appeal began, he wrote a letter that gave WLT supporters an insight into what’s at stake in his “forest motherland”.

“This is an area of India where land can only be owned by communities, and for long we A’chik Mande had managed to live off it sustainably, in a cycle that allowed nature to replenish. But now things are changing. Recent developments and the risk that mining projects could arrive one day means we have to be proactive, and protect more of this important land.”

– Rangku Sangma, Chief Forest Officer at the Garo Hills Autonomous District Council

Rangku’s wish to see his forest home protected has now been granted. The Garo Green Spine has seen community-owned reserves established before, but the 35,000 ha of land protected under community plans is a new development. These plans, designed in consonance with wildlife movement and biodiversity conservation, will help to foster responsible resource use – a continuation of A’chik Mande tradition that enshrines communal and sustainable management of forests through customary law.

The A’chik Mande have remained the stewards and beneficiaries of protected areas in the Garo Green Spine since the project’s inception. A diverse range of support has also been provided to these communities over the years: WTI have truly gone above and beyond by supplying everything from computer centres and sanitation facilities to suspension bridges, water tanks, and training for beekeepers. Your donations will allow WTI to continue enriching lives in Garo through education, healthcare, and sustainable livelihood support.

550 people have benefited from free medical checks since 2018 alone. Credit: WTI / Upasana Ganguly

“Thank you to everyone who has supported our appeal to secure the last link in the chain for WTI’s Garo Green Spine project. You’ve ensured that wildlife can move freely through this landscape, by working with local communities to protect and restore this vital habitat in one of Earth’s most threatened biodiversity hotspots.”

– Gwynne Braidwood, Conservation Programmes Officer at WLT