A male Ruff in breeding plumage, one of our many passage and summer migrants that will benefit from our Connecting Ukuwela appeal. Credit: Scott Guiver

This spring, you can help our partner Wild Tomorrow connect and expand the Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve (GUNR) with our appeal Connecting Ukuwela. This will benefit Lions (Panthera leo), Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), and Elephants (Loxodonta africana) – as you’d likely expect – but also many species familiar to keen birders in the UK.

Each spring and autumn, many migrating birds arrive in the UK. In late spring, over the rooftops of our towns, there is the aerobatic flight and “screaming parties” of the Common Swift (Apus apus). Far from the towns, our conifer forests and heathlands become the summer home of the nocturnal European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), a secretive bird more often heard than seen. Meanwhile, our coastlines and estuaries become the feeding site for large flocks of waders, which include Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia). Near these estuaries, the UK’s reedbeds and marshes are revisited by warblers, such as the Sedge Warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), characterised by its smart plumage and complex, richly varying song.

A Sedge Warbler (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus) singing in the South Essex marshes. Credit: Scott Guiver

While some of these migrating birds stay for the summer, others such as the Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea) are usually seen in autumn as they return southwards to Africa. There are no hard-and-fast rules with bird migration. For example, most Ruff (Calidris pugnax) migrate between Scandinavia and Africa, but a small number (under a 1,000) overwinter in the UK. An even smaller number breed here, with records of just 13 breeding females. However, as the days draw in towards autumn, the summer migrants leave our shores. Where do they go?

A pair of Spotted Flycatchers (Muscicapa striata) waiting on their perches for passing insects. In August, they leave the UK on a staggering journey of over 4000 miles across the Sahara Desert to tropical Africa. Credit: Scott Guiver

For hundreds of years, the autumn disappearance of migratory birds was a complete mystery. Aristotle suggested that Redstarts (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) turn into Robins (Erithacus rubecula), while the 17th Century scholar Charles Morton thought our summer migrants overwinter on the moon. The true state-of-affairs – that these migrants head south to overwinter in Africa – is by no means less magical. Take the Willow Warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus) for instance. Just months after hatching, juvenile Willow Warblers can travel an astonishing 5000 miles to reach their wintering grounds in sub-Saharan Africa.

Unfortunately, many of our summer visitors are becoming rarer with each passing year. For example, the Common Swift is increasingly uncommon, with population declines of 60% since 1990. It is now a Red-listed species in the UK. A similar fate has befallen the Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) which has declined by 65% since the early 1980s. Its iconic two-tone call, once a familiar staple of any countryside walk, is now one you rarely hear. Why are these declines happening and what can we do?

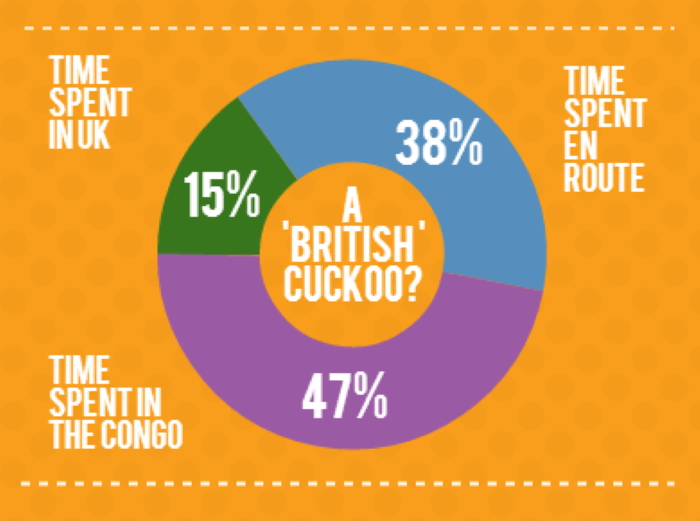

It is tempting to think of our summer visitors as “British birds” and to investigate the cause of their declines through this lens. While there is merit to this – we of course need to consider their breeding habitat in the UK and how this has changed – it risks missing out the importance of their migration, stop-over sites, and overwintering habitat. In fact, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) have shown, through satellite tagging, that Cuckoos in particular may be better thought of as “African birds which make a short and dangerous excursion to northern climes, purely for the purposes of breeding”. As such, we have a shared responsibility for the summer, wintering, and passage grounds of our summer visitors. While a lot of focus has been put on their breeding habitat, we also need to protect their overwintering habitat. This year, through our appeal Connecting Ukuwela, you can help our partner Wild Tomorrow do just that.

A re-think in how we consider our summer migrants. This is an infographic from satellite tagging of “Chris the Cuckoo”. Credit: British Trust for Ornithology (BTO).

In KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, our partner Wild Tomorrow is seeking to expand the Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve. Set up in 2021, this reserve is host to a rich tapestry of habitats – wetlands, forest, and savannah – that provide critical overwintering habitat for our summer migrants. Kevin Jolliffe, GUNR’s Reserve Manager and keen birder, keeps detailed records of the reserve’s feathered visitors. In total, he has recorded 22 UK Amber and Red-list species on the reserve. Several of these, like the Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), are very rare visitors to the reserve. Others, like the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and Little Tern (Sternula albifrons) arrive in small numbers every year, making use of the reserve’s lush wetlands. And then there are those waders seen in large numbers, including Common Greenshank.

A Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia) photographed in Western Africa while on passage migration. Credit: Scott Guiver

Excitingly, Kevin has also started ringing the reserve’s waders, in particular Curlew Sandpipers and Wood Sandpipers. This project, conducted with the University of KwaZulu-Natal, will give a greater insight into the movements of these wonderful birds.

By working together, we can safeguard the wintering grounds of these extraordinary migrants. Our Connecting Ukuwela appeal will help to secure such a future, by providing Wild Tomorrow with the funds to expand their Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve and protect the overwintering habitat of these incredible species. Learn more about this appeal, and how you can help, here.

Donate today and see your donation matched to double its value!