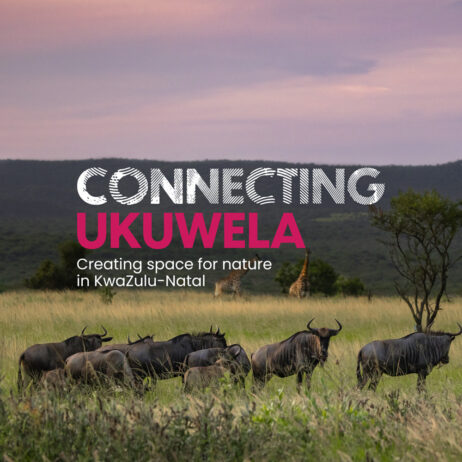

A group, or rather a “committee”, of White-backed Vultures resting in a tree. Unlike other species of Vulture, they are very social. Credit: Chantelle Melzer

With our spring appeal, Connecting Ukuwela, you can support our partner Wild Tomorrow to connect and expand their Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve (GUNR): a wildlife corridor in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. As you might imagine, this wonderful project will bring benefits for Lions (Panthera leo), Elephants (Loxodonta africans), and Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). But, in the skies far above, Eagles and Vultures will also feel the change. Read on to find out more about which of these raptors will benefit.

Martial Eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus)

After a long morning soaring on updraughts, a Martial Eagle finally sights its quarry. Far below, it sees the distant speck of a young male Impala (Aepyceros melampus) who is standing uncertainly, separated from its herd. Seizing this opportunity, the Eagle swiftly tucks its wings close-in against its body and, tilting downwards, it dives. Seconds later, it is plummeting at 230 kilometres per hour, the Impala its next meal.

One of Africa’s largest and most fearsome predators: the Martial Eagle. Credit: Hans Veth/Unsplash

From this, it is easy to see why the Martial Eagle, Africa’s largest and most powerful bird of prey, earned its nickname “the leopard of the air”. Most hunts, however, are not nearly as dramatic. While it can spot prey from a staggering 5 km away, a staple of its diet – Monitor Lizards (Varanus sp.) – are typically caught via a short descent from nearby trees. Indeed, it owes its reputation as a fearsome predator as much to its diverse diet as its exceptional hunting abilities. A single individual has been known to have preyed on over 170 different species, everything from Banded Mongooses (Mungos mungo) and Vervet Monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) to Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris).

In a cruel twist of irony, the hunting prowess that once enabled this enigmatic raptor to flourish across Africa has now made it the subject of intense persecution and is leading to its demise. In South Africa, there are only around 600-800 breeding pairs left and it is classified as Endangered. Fortunately, they are resident on the GUNR, where they can be seen soaring on updraughts, the parent birds teaching the juveniles how to hunt.

Southern Banded Snake Eagle (Circaetus fasciolatus)

In a woodland by an estuary, a female Southern Banded Snake Eagle is flying back to its nest, the bright emerald-green body of a Spotted Bush Snake (Philothamnus semivariegatus) clasped firmly in its talons. For a casual observer, the nest is hard to find. Well-hidden 10 metres up a tall tree, it has been concealed from below by a lining of leaves and from above by a hanging curtain of canopy creepers. When the female returns, the chick starts to clamour and the male, relieved of its duties as sentinel, flies off to hunt. The female then precedes to feed the snake to its chick.

Stocky but powerful: the Southern Banded Snake Eagle. Credit: David Tattersley/Flickr

The Southern Banded Snake Eagle is Critically Endangered in South Africa and only occurs in northern KwaZulu-Natal. They are restricted to this region because their habitat is disappearing. They need sites where coastal forest borders grassland and marsh. Excitingly, this tapestry of habitats is provided by the GUNR, where two pairs are currently nesting. Given that just 50 Southern Banded Snake Eagle adults are left in South Africa, this reserve is extremely important for their survival. With our appeal Connecting Ukuwela, you can help to expand this reserve and thus secure a thriving future for this enigmatic raptor.

White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus)

A White-backed Vulture is circling over a savanna, scanning the ground for a carcass. Far below, it sees a clan of Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) running towards the remains of a dead Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer). With other scavengers approaching, it is too dangerous for a White-backed Vulture to descend to a carcass alone. For this reason, once a carcass is spotted, they start wheeling in the sky to signal the discovery to others. They then descend together, dropping onto the ground and approaching the carcass while making pig-like squealing noises. Since their beaks are not capable of puncturing tough hide, they target those areas opened up by other scavengers. Once they have gorged themselves, they rest on the ground, temporarily unable to fly.

The White-backed Vulture. Credit: Lip Kee/Flickr

The White-backed Vulture is rapidly disappearing from the skies above Africa. In the last 40 years, it has become Critically Endangered with population declines from 63-89%, according to BirdLife International. The main culprits behind these declines are habitat loss, poisoning, electrocution from power lines, drowning in farm reservoirs, and trapping for traditional medicine. This is a serious loss because Vultures, unlike mammalian scavengers such as Spotted Hyenas, have powerful stomach acids that can neutralise any harmful bacteria found in carcasses and so prevent the spread of disease.

It is revealing that White-backed Vultures have been shown to consistently avoid areas of high human activity when selecting nesting sites, often choosing protected reserves instead. This is why the expansion of sites such as the GUNR, where they are often seen feeding on carcasses, is so important. Together, we can create a future where these enigmatic birds of prey are not a rare sight in the skies over South Africa, but a wonderfully common one.

Our Connecting Ukuwela appeal will help to secure such a future, by providing Wild Tomorrow with the funds to expand their Greater Ukuwela Nature Reserve. The first £50,000 donated will be matched by a generous supporter, meaning that your donation will be doubled and a £10 donation will be worth £20 towards this incredible project.

Donate today and see your donation matched to double its value!