OBITUARY

JOHN BURTON

By journalist, author, WLT ambassador and member of the WLT council Simon Barnes

John Burton, co-founder of the World Land Trust, died on Sunday May 22 2022 – World Biodiversity Day, as it happens. He was 78. Don’t worry, he already has a monument. It takes the form of more than a million acres of thriving, teeming wild land.

How did that come about? The first answer is that it all began on May 5 1989 at Syon House Butterfly House when the World Wide Land Conservation Trust — now the World Land Trust — was launched. The second answer is that it all began in John’s childhood in South London.

At the age of six he was making weekly bus-trips to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, just him and his friend Tony Hutson. In his teens he was bird-ringing, taking part in surveys for foxes and badgers, recording bird migration, working on a project to air-lift turtles to the Caribbean and completing a study of hedgehogs.

He did more than study them. He also caught hedgehogs in Biggin Wood and sold them to Harrod’s at five bob a time, a practice now rightly regarded as reprehensible. Beside all this, his official schooling was peripheral. He was educated in forests and bird observatories and the great museum.

He joined the Natural History Museum as an assistant information officer straight from school, and also played the tuba in an oompah band. He then went freelance and wrote natural history books; he has more than 40 titles to his name. And he was the first wildlife consultant to a new organisation called Friends of the Earth.

Conservation was changing. There was growing awareness of the surrounding extinction crisis: and with it came new and radical ideas of what to do about it. John was in the forefront. It was not enough just to study wildlife: we had to take major steps before we lost it all.

He was headhunted by the Fauna Preservation Society and was their chief executive at 31. He then founded TRAFFIC, an organisation that monitors the illegal trade in wildlife, one of the biggest illegal trades after drugs, arms and people. For a good while he ran both organisations at the same time, a back-breaking load.

This ended in 1987, when he stepped down to write the excellent Rare Mammals of the World. But before that, he had hired Viv Gledhill as his conservation assistant back in 1975. She then went on to work with another great conservationist, Sir Peter Scott, founder of what is now the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust at his headquarters in Slimbridge.

John and Viv met up again when separately attending a wildlife conference at Kilaguni Lodge in Kenya, and that was that. They were married in 1980 and one of the great teams in conservation was conformed: John always as the front man, Viv as the organiser who made it all possible.

They soon showed how effective they could be. A great friend and conservation colleague, Jerry Bertrand, was president of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. He came up with the radical notion that the people of New England should look after their migrant birds – by giving money to preserve their wintering grounds. Places like the rainforest in Belize.

The Burtons agreed to help him. They were given US$15,000 with instructions to turn this into US$50,000 in a year. They reached this target within six weeks of launching – and at the same time the organisation that became the World Land Trust was formed and a pattern of action was established.

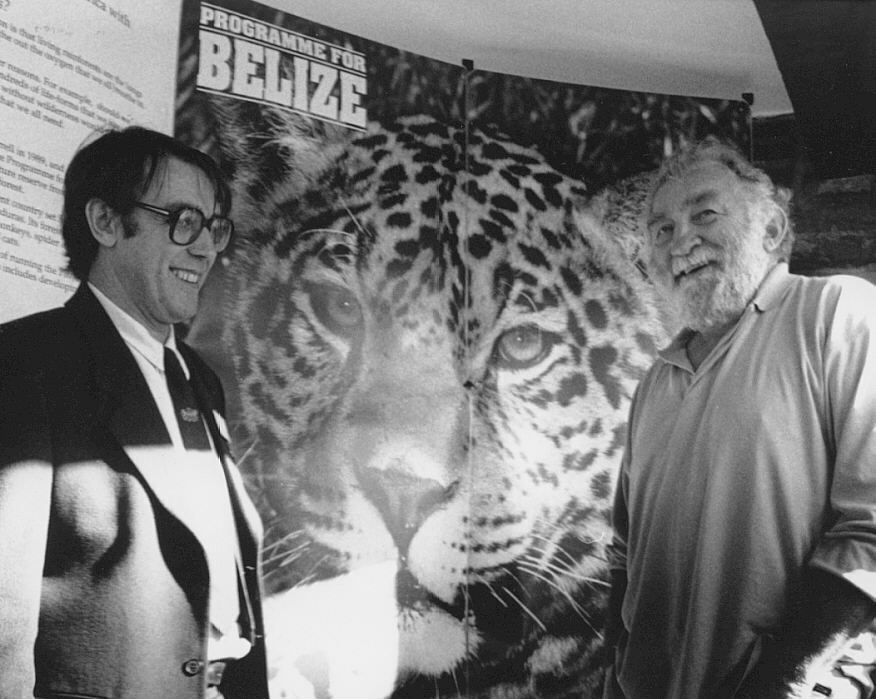

John Burton with David Bellamy at the launch of Programme for Belize

And right from the start it was about partnership. WLT worked with the local organisation Programme for Belize. WLT raised the money to buy rainforest: but it was bought and owned by the organisation on the ground in Belize. It was their project: WLT just helped it along.

The campaign was based on a notion of breathtaking simplicity: buy an acre of rainforest for £25. A real acre in a real place. It caught the public imagination: and almost at once WLT was moving forwards, next to a project in Costa Rica, then to an island in the Philippines, after that to REGUA, a rainforest restoration project in Brazil – and on it went.

WLT was founded on an idea of simple genius: that if you take control of the land everything that lives there is safe. If you can save the land you can save the species: all the species that use the place. John and Viv led WLT onwards, taking on projects in more than 30 countries.

When I moved to Suffolk I found that my neighbour, Pete Wilkinson, had been Greenpeace’s man in the Antarctic. We went for a pint at the nearby Sibton White Horse and John, who lived round the corner, came along too. It was a great meeting. It was at once apparent that John was a genuine polymath with a love of spiralling conversation and a marked taste for contrarianism: the novels of Anthony Burgess, the comic songs of Tom Lehrer, Italian opera, how to look after a baby hare, how to catch hedgehogs, the traditional musical instruments of Romania, climate, the population crisis, the shortage of insects, horror films, toads, growing raspberries and the irrefragable fact that elephant shrews are infinitely more fascinating than lions.

It was a conversation that lasted for the next 23 years, and it took place in pubs and restaurants, round campfires, in jungle huts, on mountain-tops, in the African savannah and once over three days in an emerald mining camp.

At the time I was writing books about wildlife while working for The Times, doing the unusual double of chief sportswriter and wildlife columnist. My first trip with WLT and John was to Belize: a surreal experience that also involved a celeb writer from Hello! magazine, a female fashion photographer, a male make-up artist and the film star Darryl Hannah (Roxanne, Splash, Kill Bill etc. – also The Attack of the Fifty Foot Woman).

It was the first of many trips, though none was madder than the first, A few years later I was invited to become a WLT council member. John said: “But I don’t suppose you can accept, because it would compromise your objectivity.” “What objectivity would that be, JB?”

So I accepted, and travelled and wrote about WLT many times and it became a life-defining cause. I discovered the way the WLT worked: it was about partnership with the people who lived in the place and looked after the land. The partnerships were based on friendship, trust, honesty, transparency – and a shared and total love for the wild places we were all trying to save. It was that trust that consistently allowed the WLT to punch way above its weight.

Simon Barnes with Vivek Menon (Executive Director of WTI) and John Burton, inspecting land for potential elephant corridors.

Roger Wilson, who had worked on many projects in extreme conditions before joining WLT, articulated the guiding principle of what WLT does: the local organisation is in charge. They are the boss, it’s their show. WLT is just the humble fund-raiser. Of course, John also did a great deal of mentoring: helping these small organisations to survive and prosper in difficult and often hostile circumstances. The international nature of WLT brought strength and kudos to the local organisation on the ground: if all these foreigners care, it must be important.

John was a great champion of the underdog and the under-appreciated. He was banned from the United States for the support he gave to the Iran Cheetah Society, which he saw very much as scar of honour. He had a huge affection for the Chaco areas of Paraguay, a wild place in which there are still uncontacted tribes. And he took a great shine to Armenia and the wild mountainous landscapes of the Caucasus.

He suffered from a bout of cancer and got through it. When the chemo was done and he was allowed to travel again, his first trip was to Armenia and I went with him. There we spent time with the great people of the local organisation, Foundation for the Preservation of Wildlife and Cultural Assets.

They were keen to show us some land that they believed WLT should invest in. For various logistical reasons, John was unconvinced. So we went there: a day that began in the wild rose gardens at the mountain’s foot, up through the impossible colours of the alpine meadows, and onto the tops and the glorious inch-high vegetation of limestone pavement.

It was a perfect place, and we all resolved to do our best to safeguard its future. And that’s the way I shall remember John best: up there on a mountain top, panting hard, with all this impossible glorious land all around him and inside him a diamond-hard will to keep it safe.

He left WLT in 2019 after 30 years of work, a workload shared with Viv. He was involved in a number of other wild projects, but alas, the cancer struck again. He died at home in Suffolk. The million or so acres are still thriving,

John Burton with his John Spedan Lewis Medal awarded by the Linnean Society for his innovative contributions to conservation.